The American Dream Is Dead

The Startup (Medium)

May 4, 2018

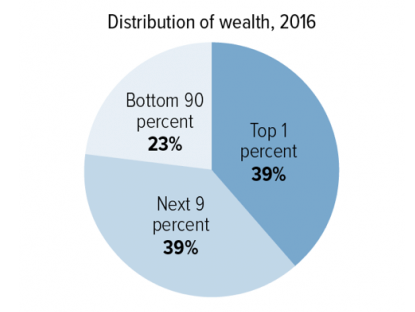

Georges Abi-HeilaThe top 0.1% owns as many assets, as the bottom 90%. And it’s getting worse.

One of America’s founding myth is that of the “self-made man”: the idea, that with enough work & dedication anybody can climb the social ladder and become wealthy. Or at least be better off, than his or her parents.

Well, that’s complete bullshit.

Data shows, that the most important drivers of one’s living standard are determined at birth: most of the people, who are poor, are so, because they made the mistake of being born to the wrong parents.

“No matter, what your educational background is, where you start, has become increasingly important for where you end.”

- Michael D. Carr, economist at the University of MassachusettsNow the goal of this article is not to languish and complain. By providing a fact-based analysis of the unfairness of our society, I aim to foster empathy and gratitude in the reader’s mind. Acknowledging the luck, you have, is the starting point towards greater generosity and happiness. Let’s dig into the facts!

We live in a profoundly unfair society

…and it’s getting worse every year.

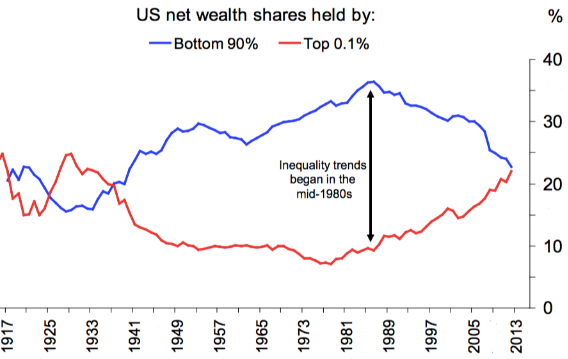

Most of the nation’s economic growth over the past 30 years has gone to the top 0.1%. Inequality is now approaching the extreme level, that prevailed prior to the Great Depression.

The top 10% of households owns ~80% of the wealth.In fact, inequality is so high, that a third of the population has no wealth at all and the top 0.1% owns as many assets, as the bottom 90%.

Raw statistics are perfect tools for transmitting the truth of facts, but they lack the emotional baggage, that a story can deliver. There’s nothing better, than tears, blood and immersive storytelling to mobilize people.

I’m unfortunately not very good at that, but I can still rephrase the statistics: if the US was a village of 1000 people, there’s 1 guy, that has more money, than 900 other villagers combined…

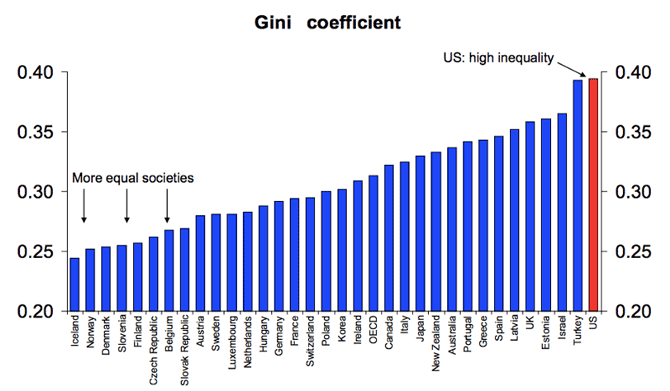

The top 0.1% owns as many assets, as the bottom 90%.We can manipulate numbers and discuss hypotheses as much, as we’d like: the reality is staggering. Research centers, in their vast majority and coming from all political backgrounds, have drawn the very same conclusion: the US is — by far — the most unequal society in the developed world. And things are getting worse every year.

The Gini coefficient is a number between 0 and 1, where 0 represents perfect equality and 1 perfect inequality (one person has all of the country’s income).Now a lot of us can cope with that, if there are good chances of improving our situation. If my household’s finances are better, than my parents’, the society, I’m living in, would have enhanced my well-being.

That’s actually one of the cornerstones of modern capitalism: inequalities are accepted as long, as the possibility of betterment exists. We tolerate unfairness as long, as there are good chances of improving our condition. The question is: what are the chances?

Moving up is a lottery

…and most of us lose.

To better understand inequality of opportunity, social scientists and economists have increasingly shifted their attention to intergenerational mobility. By assessing the strength of the association between parents’ and offsprings’ income, we can get an approximation of the possibilities given to each generation on their quest for happiness.

So is social mobility a plausible reality in modern-day America?

Well, the answer is quite simply: no.“The probability of ending where you start has gone up, and the probability of moving up has gone down.”

- Raj Chetty, economist at the National Bureau of Economic ResearchAccording to a research paper by the National Bureau of Economic Research, US social mobility fell by more, than 70% in the past half century. If you feel, that it’s getting harder to get ahead, you’re not being delusional: in 2016 about half of 30-year-olds earned less, than their parents at the same age.

Social mobility is the exception, not the norm.Another way to look at this is to study income growth. Income growth is an interesting metric, because it’s a proxy for “better quality of life”: with higher income comes increased purchasing power and better standards of living.

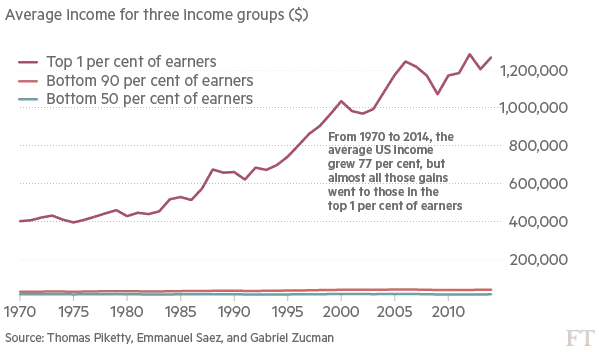

So how is the growth of income distributed among the population? Well, since 1979 all of the income gains have been captured by the top 1% and wages have stagnated for everybody else. This is one of the most depressing statistic, I’ve ever read: it basically means, that most households in the US have not seen any increase in their revenue since 30 years!

With remarkable consistency the superrich have managed to capture all the productivity gains made by American workers and convert them to skyrocketing earnings…

For the last 40 years income and wages have stagnated for most Americans.The fact is, wealth is so unevenly distributed, that one could argue, that the US is a failing democracy: power is entirely held by an elite, that’s never renewed and that captures all of the income gains.

But what does the 1% think about that? Do they feel empathy and gratitude? Do they recognize their position being — for a great part — the result of luck and unfair advantages?

Money makes people selfish

…the wealthier you are, the less empathetic you become.

Saying, that wealth grants a lot power in today’s capitalistic societies, is no great insight. Wealth is, what makes you beautiful, what reduces your stress and daily fatigue, what grants you social prestige and education, what gives you time and freedom of choice. Wealth is a big deal.

But does wealth affect your behaviour? In other words, do emotional responses and rational thinking change, when income increases? A team of scientists from UC Berkeley’s Institute of Personality and Social Research did a series of fascinating experiments on this topic.

The “Cookie Monster” They first tried to measure, if individuals feel more important, than others, when put in a position of power.

Who took the fourth extra cookie? In almost all cases it was the person, who’d been made the leader. And they were more likely to eat with their mouths open and dropping crumbs. It just seems, that when put in a position of power, we tend to be more impulsive and less empathetic.

This pattern of increased selfishness has been consistently observed across similar studies.

The “Rude Driver” The goal here is to check, if there’s a difference in driving behavior between the rich and the poor.

The researchers sat at specific crossroads, observing each driver’s attitude, as an accomplice appeared on the edge of the curb, while cars approached. The results were astonishing: people driving luxury cars, like BMWs and Mercedes, yielded to pedestrians twice as less, as drivers of less expensive cars.

They also watched a 4-way stop intersection, noting, when drivers cut in front of others, when it was not their turn. The results? The more expensive cars were far more likely to jump their turn.

“You just see this huge boost in a driver’s likelihood to commit infractions in more expensive cars.”

- Paul K. Piff, Professor of Psychology at UC Berkeley

The “Stoic Listener” This experiment’s objective is to assess, whether level of empathy is affected by how powerful the subject considers himself.

Subjects sat down in a face-to-face conversation with people, who talked about experiences, that had caused them suffering. The listeners’ responses were measured 2 ways: first by self-reported levels of compassion and second by electrocardiogram readings to determine the intensity of their emotional response.

The participants were also asked to rank themselves on questions measuring personal strengths (“I can get people to listen to what I say”) and weaknesses (“My wishes do not carry much weight"). That allowed the researchers to place them on a “sense of power” scale.

The findings were hugely insightful: Participants with a higher sense of power were far more likely to turn a blind eye to their partner’s story. More precisely, they “experienced less distress, less compassion and exhibited greater autonomic emotion regulation”.

The “Blind Observer” This last study further confirms previous conclusions. Participants were shown images of suffering — kids with cancer, for instance. People with a greater sense of power had less activation of a part of the brain, that helps us connect to one another. To put it bluntly, they just seem less sensitive to what others are feeling.

“When a person is suffering, upper-class individuals perceive these signals less well on average. They tend to underestimate the distress in their social environments.”

- Jennifer E. Stellar, Professor of Psychology at UC BerkeleyUltimately it turns out, wealth is a very good predictor for unethical behavior and reduced empathy. So what’s happening here? Do you magically become ungrateful & greedy, when you buy a new Porsche? What are the psychological mechanisms at play?

Money makes you feel special

…the richer you are, the more entitled you feel.

One thing’s for sure: the wealthy don’t seem to fully recognize their good fortune. If they did, the level of redistribution would be far greater, than what it is and tax cuts wouldn’t be so popular among high income brackets.

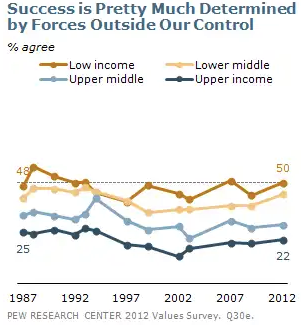

It also seems, that rich and poor largely disagree on factors, that lead to success: according to a survey by the Pew Research Center People with high income are much more likely to attribute success to hard work rather, than to factors like luck or being in the right place at the right time.

Poor and rich people largely disagree on the

factors of success.That’s troubling, because we saw earlier, that socio-economic background is the main predictor of an adult’s income and that social mobility is the exception, not the norm.

Most behavioral and social scientists know, that our brains are fundamentally flawed and that our opinions are not as rational, as we might think. Human cognition gives us great insights into why wealthy people tend to underestimate the role of luck in their careers.

Hindsight bias …also known as the “knew it all along” effect

This term describes our tendency to rationalize unpredictable events. Humans have a natural inclination, after an event has occurred, to see it as having been predictable, despite there having been little or no objective basis for predicting it.

Physicians recalling clinical trials, historians describing outcomes of battles, judges trying to attribute responsibility of accidents: the examples are numerous.

All of a sudden people were telling me, I was a born writer. This was absurd. […] What were the odds?

- Michael Lewis recalling reactions after the publishing of his first book, “Liar’s Poker”.This bias operates with particular force for unusually successful outcomes. People don’t like to hear success explained away as luck — especially successful people. As they age and succeed, people feel, their success was somehow inevitable.

Availability heuristic …also known as the “If I remember it, it must be important” effect

When making decisions or assessing situations, we tend to give a lot of importance to events, we immediately recall; thus minimizing the role of things, we forgot or never thought about. Under the availability heuristic, people tend to heavily weigh their judgments toward more recent and concrete information. One practical example is, that opinions are biased toward the latest news.

A successful career is a subtle combination of multiple factors, such as talent, capacity of concentration, amount of work, random encounters, family background, mental resilience, living environment, etc. The thing is, some of those factors are more frequent and easier to perceive, than others.

We’re all vividly aware of how many hours we spend working every day and how dedicated (or not) we are. We can effortlessly recall the last time, we pulled an all-nighter to deliver on time and how difficult this "hugely important, but reall complicated" project was. But do you perceive, how lucky you are, not to have been born in Mozambique? How privileged you are to have a college degree? How improbable was your encounter with your business partner? How blessed you are to be healthy and without handicap?

In the construct of our life stories we unconsciously shrink crucial, but abstract factors. Unknowingly, we use mental shortcuts, that lessen the importance of everything, that’s not linked to our close environment. That’s, why we tend to largely overestimate the impact, we, as individuals, have on our life paths.

In an existence led by randomness humans tend to overemphasise their personal performance, because they’re biased towards their own day-to-day experience.

Negative memory …also known as the “we don’t care about planes, that arrive on time”

A well known cognitive bias is, that we recall negative events more frequently and more intensely, than positive ones. For example, it’s been proven, that we’re usually more upset about losing $50, than we are happy about gaining $50. The same applies to negative feedback, delayed flights, lost games, etc. The effect of those negative experiences is much more powerful, than their positive counterparts.

“Almost everyone remembers negative things more strongly and in more detail.”

- Clifford Nass, professor of communication at Stanford UniversityFrom an evolutionary perspective this is justified: survival requires urgent attention to possible bad outcomes (and less urgent to good ones). But in today’s world it’s a major flaw in our decision-making capabilities. Looking back at our life choices, we’ll always be more aware of the hurdles and obstacles, we faced, than of the things, that helped us. Think of it as cognitive ungratefulness!

Recognize your luck and practice empathy!

…we’re not as great, as we think, we are.

I feel, that we’re at a tipping point. Inequalities are at a record high, social mobility is at a record low and our elite’s moral values don’t seem to converge towards better redistribution or benevolent sharing.

The extremely wealthy, besides concentrating the vast majority of assets and income gains of the country, fail to truly recognize the role of luck in their good fortune.

This is dangerous, because it’s a breeding ground for desperation and hopelessness. When people lose faith in the possibility of improving their condition, when they realize, the American Dream has become nothing, but a myth, they will resort to extreme means. The subtle combination of political lies, corporate story-telling and public ignorance, that has maintained social peace, may not last forever.

If a tiny minority has all the wealth, if income is stagnating for 9 citizens out of 10, if chances of climbing are minuscule, isn’t rebellion justified?