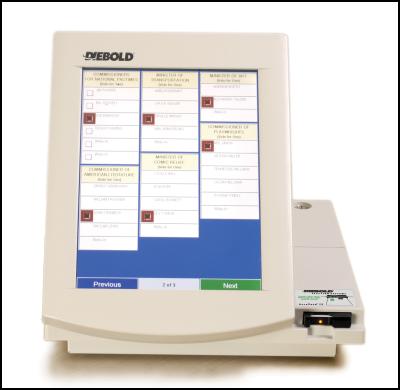

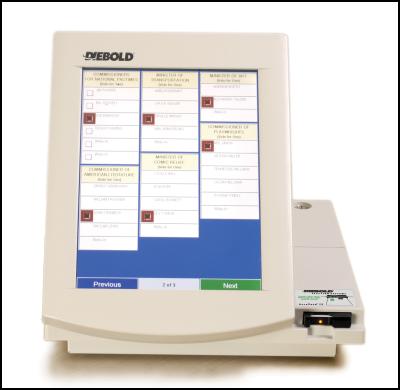

A Diebold touchscreen voting machine

Makers of the walk right in, sit right down, replace ballot tallies with your own GEMS vote counting program.

Scoop, New Zealand

(original here, server overload possible, so be patient)

July 8, 2003

By Bev Harris

(author of the soon to be published book

Black Box Voting: Ballot Tampering In The 21st

Century)

A Diebold touchscreen voting machine

Makers of the walk right in, sit right down, replace ballot tallies with your own

GEMS vote counting program.

For both optical scans and touch screens operating using Diebold election systems, the voting system works like this:

Voters vote at the precinct, running their ballot through an optical scan or entering their vote on a touch screen. After the polls close, poll workers transmit the votes that have been accumulated to the county office. They do this by modem. At the county office there is a "host computer" with a program on it called GEMS. GEMS receives the incoming votes and stores them in a vote ledger.

But then, we found, it makes another set of books with a copy of what is in vote ledger 1. And at the same time it makes yet a third vote ledger with another copy. The Elections Supervisor never sees these three sets of books. All she sees is the reports she can run: Election summary (totals county-wide) or a detail report (totals for each precinct). She has no way of knowing that her GEMS program is using multiple sets of books, because the GEMS interface draws its data from an Access database, which is hidden.

And here is what is quite odd: On the programs we tested, the Election summary (totals county-wide) come from the vote ledger 2 instead of vote ledger 1. Now think of it like this: You want the report to add up ONLY the ACTUAL votes. But, unbeknownst to the election supervisor, votes can be added and subtracted from vote ledger 2, so that it may or may not match vote ledger 1. Her official report comes from vote ledger 2, which has been disengaged from vote ledger 1.

If she asks for a detailed report for some precincts, though, her report comes from vote ledger 1. Therefore, if you keep the correct votes in vote ledger 1, a spot check of detailed precincts (even if you compare voter-verified paper ballots) will always be correct. And what is vote ledger 3 for? For now, we are calling it the "Lord Only Knows" vote ledger.

From a programming standpoint there might be reasons to have a special vote ledger that disengages from the real one. From an accounting standpoint using multiple sets of books is NOT OKAY. From an accounting standpoint the ONLY thing the totals report should add up is original votes in vote ledger 1. Proper bookkeeping NEVER allows an extra ledger that can be used to just erase the original information and add your own. And certainly, it is improper to have the official reports come from the second ledger, the one, which may or may not have information erased or added.

Detailed Examination Of Diebold GEMS Voting Machine Security (Part 1)

Let's go into the GEMS program and run a report on the Max Cleland/Saxby Chambliss race! (This is an example and does not contain the real data.) Here is what the Totals Report will look like in GEMS:

As it stands, Cleland is stomping Chambliss. Let's make it more exciting! The GEMS election file contains more, than one "set of books." They are hidden from the person running the GEMS program, but you can see them, if you go into Microsoft Access. You might look at it like this: Suppose you have votes on paper ballots and you pile all the paper ballots in room one. Then you make a copy of all the ballots and put the stack of copies in room 2. You then leave the door open to room 2, so that people can come in and out, replacing some of the votes in the stack with their own. You could have some sort of security device that would tell you, if any of the copies of votes in room 2 have been changed, but you opt not to.

Now suppose you want to count the votes! Should you count them from room 1 (original votes)? Or should you count them from room 2, where they may or may not be the same as room 1? What Diebold chose to do in the files we examined was to count the votes from "room 2".

Illustration:

If an intruder opens the GEMS program in Microsoft Access, they will find that each candidate has an assigned number:

One can then go see how many votes a candidate has by visiting "room 1", which is called the CandidateCounter:

In the above example "454" represents Max Cleland and "455" represents Saxby Chambliss. Now let's visit Room 2, which has copies of Room 1. You can find it in an Access table called SumCandidateCounter:

Now let's put our own votes in Room 2! We'll put Chambliss ahead by a nose, by subtracting 100 from Cleland and adding 100 to Chambliss. Always add and delete the same number of votes, so the number of voters won't change.

Notice that we have only tampered with the votes in "Room 2." In Room 1 they remain the same. Room 1, after tampering with Room 2:

Now let's run a report again! Go into GEMS and run the totals report! Here's what it looks like now:

Now, the above example is for a simple race using just one precinct. If you run a detail report, you'll see that the precinct report pulls the untampered data, while the totals report pulls the tampered data. This would allow a precinct to pass a spot check.

Detailed Examination Of Diebold GEMS Voting Machine Security (Part 2)

At least a dozen full installation versions of the GEMS program were available on the Diebold FTP site. The manual, also available on the FTP site, tells that the default password in a new installation is "GEMSUSER." Anyone, who downloaded and installed GEMS, can bypass the passwords in elections. In this examination we installed GEMS, clicked "new" and made a test election, then closed it and opened the same file in Microsoft Access.

One finds where they store the passwords by clicking the "Operator" table. Anyone can copy an encrypted password from there, go to an election database and paste it into that.

Example: Cobb County Election file

One can overwrite the "admin" password with another, copied from another GEMS installation. It will appear encrypted; no worries, just cut and paste! In this example we saved the old "admin" password, so we could replace it later and delete the evidence that we'd been there. An intruder can grant himself administrative privileges by putting zeros in the other boxes, following the example in "admin."

How many people can gain access? A sociable election hacker can give all his friends access to the database, too! In this case they were added in a test GEMS installation and copied into the Cobb County Microsoft Access file. It encrypted each password as a different character string, however all the passwords are the same word: "password." Password replacement can also be done directly in Access. To assess how tightly controlled the election files really are, we added 50 of our friends; so far we haven't found a limit to how many people can be granted access to the election database.

Using this simple way to bypass password security, an intruder or an insider can enter GEMS programs and play with election databases to their heart's content.

Detailed Examination Of Diebold GEMS Voting Machine Security (Part 3)

Britain J. Williams, Ph.D. is the official voting machine certifier for the state of Georgia and he sits on the committee that decides how voting machines will be tested and evaluated. Here's what he had to say about the security of Diebold voting machines in a letter dated April 23, 2003:

"Computer System Security Features: The computer portion of the election system contains features that facilitate overall security of the election system. Primary among these features is a comprehensive set of audit data. For transactions that occur on the system a record is made of the nature of the transaction, the time of the transaction and the person that initiated the transaction. This record is written to the audit log. If an incident occurs on the system, this audit log allows an investigator to reconstruct the sequence of events that occurred surrounding the incident. In addition, passwords are used to limit access to the system to authorized personnel."

Since Dr. Williams listed the audit data as the primary security feature, we decided to find out how hard it is to alter the audit log. Here is a copy of a GEMS audit report.

Note that a user by the name of "Evildoer" was added. Evildoer performed various functions, including running reports to check his vote-rigging work, but only some of his activities showed up on the audit log. It was a simple matter to eliminate Evildoer. First we opened the election database in Access, where we opened the audit table:

Then we deleted all the references to Evildoer and because we noticed that the audit log never noticed, when the admin closed the GEMS program before, we tidily added an entry for that.

Access encourages those, who create audit logs, to use auto-numbering, so that every logged entry has an uneditable log number. Then if one deletes audit entries, a gap in the numbering sequence will appear. However, we found that this feature was disabled, allowing us to write in our own log numbers. We were able to add and delete from the audit without leaving a trace. Going back into GEMS, we ran another audit log to see, if Evildoer had been purged:

As you can see, the audit log appears pristine. In fact, when using Access to adjust the vote tallies, we found that tampering never made it to the audit log at all. A curious plug-in was found in the GEMS program, called PE Explorer. Presumably, this is used to do security checks. Another function, though, is to change the date and time stamp:

Although we interviewed election officials and also the technicians, who set up the Diebold system in Georgia, and they confirmed that the GEMS system does use Microsoft Access, is designed for remote access and does receive "data corrections" from time to time from support personnel, we have not yet had the opportunity to test the above tampering methods in the County Election Supervisor's office. We used an actual data file labeled "Cobb County" for much of our testing.